Wangu wa Makeri: Unearthing the Story of the First Woman Kikuyu Chief in Colonial Kenya

Introduction

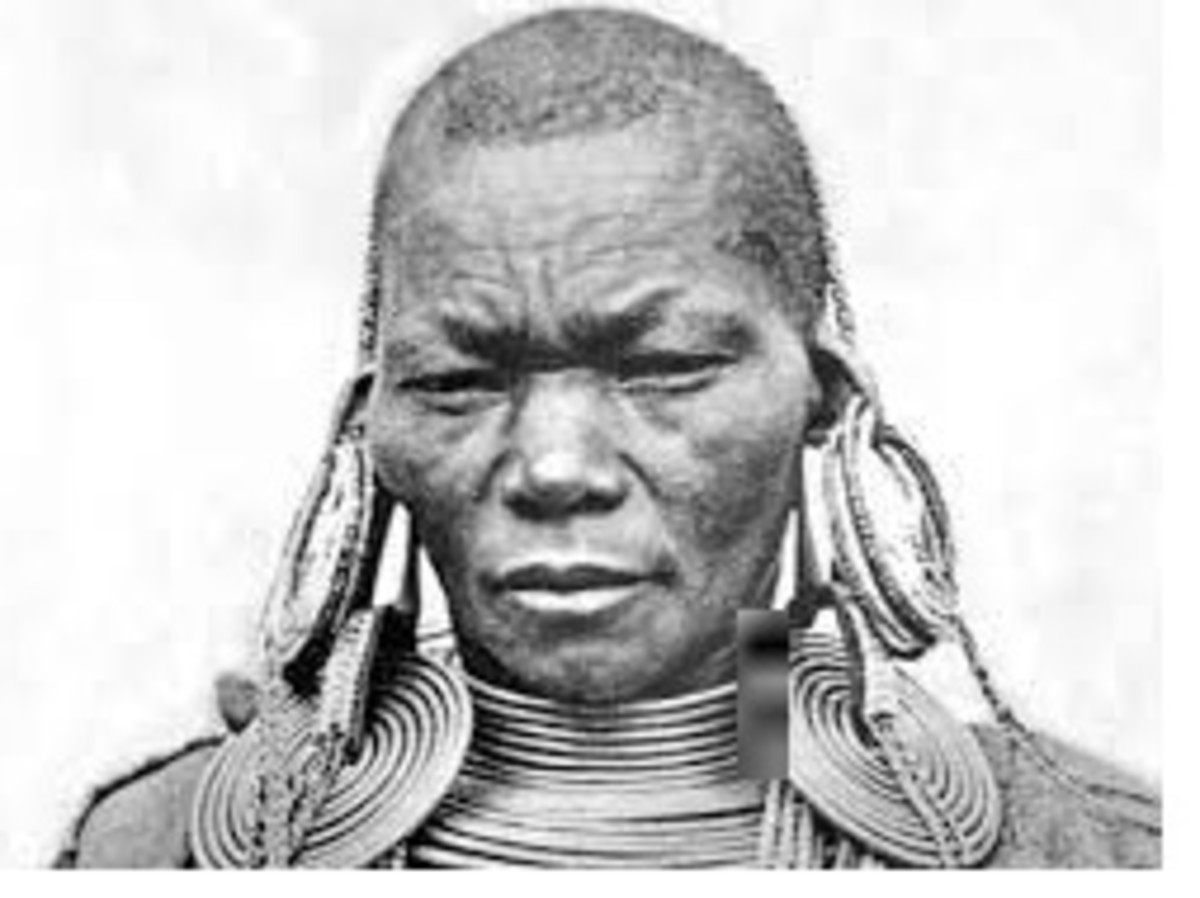

In the annals of colonial Kenya, leadership was largely a male domain. Yet, Wangu wa Makeri stands out as a remarkable figure – the first Kikuyu woman to hold the esteemed position of chief in living memory. This account offers a unique window into her life, moving beyond legend through an intimate interview with her grandson, James Makeri Muchiri, a retired teacher who holds the key to a more personal understanding of this pioneering leader.

Who was Wangu wa Makeri?

Wangu wa Makeri was the first Kikuyu female leader in living memory. This hub will bring fresh insight into the life of Wangu wa Makeri, the first woman chief in colonial Kenya.

Some people have the mistaken belief that Wangu ruled the Kikuyu during the legendary era when the Kikuyu were ruled by women. According to the legend, the women, who were also great fighters, were tricked and overthrown by men who have continued to take charge of tribal affairs to this day. This is far from the truth. If that were the case, I would not have had the privilege to interview a grandson. In fact, we would be hard-pressed to find any relatives. Wangu’s grandson is James Makeri Muchiri, a retired teacher living in Nairobi. He was introduced to me by a close relative, but due to our busy schedule, we were not able to meet for over two weeks. When we finally met, I introduced myself as a writer, artist/designer, and researcher on Kikuyu culture.

A Grandson's Voice: Unveiling Family Memories of Chief Wangu

The interview took place at 4 p.m. East African Time on October 18, 2011, at the City Square Restaurant, opp. City Hall.

This is how the interview went:

Kariuki: Seeking to clarify her lineage, I began by asking, How are you related to Wangu?

Makeri: She was my grandmother, but most of what I know I have learnt from my paternal uncle.

(I am surprised by that. I thought he would be a great grandson.

Kariuki: Popular narratives often link Wangu to another powerful figure. I enquired, People say that Wangu was Chief Karuri’s wife.

Makeri: Wangu was Makeri’s wife.

Kariuki: I had thought Makeri was her father so I clarified, Makeri? Was Makeri also a chief?

Makeri: No. Karuri had recommended him to Francis Hall to be chief, but Makeri was not interested. He thought that if he became chief, he would not have time to take care of his animals, and he would lose all of them.

Kariuki: So Makeri was a rich man then.

Makeri: Yes, that is why he thought he should not abandon his herd to become a mere chief. You see, Makeri was a great friend of Karuri. So Karuri wanted him to be chief so that when he was doing his rounds on his horse, he could rest at Makeri’s before proceeding on a tour of his jurisdiction. And you know Makeri did not have sons who could have been chiefs.

Kariuki: I thought it strange that a man of means could not have a son in those early days, so I asked, Isn't that unlikely? Well, you know Kikuyu men had more than one wife, especially rich Kikuyu men.

Makeri: Wangu was the ‘ngatha’, and her eldest son was not old enough to be appointed a chief.

Kariuki: That was my first time hearing that term and my surprise was obvious: A "ngatha?’

Makeri: that means the eldest wife. She most often, like Wangu, was the favourite one because she chose subsequent wives for him. Makeri had a total of six wives.

Kariuki: I grabbed this opportunity to ask about the wife-sharing myths that were spoken freely about the Kikuyu: Where would Karuri sleep when he visited Makeri? I mean, would he be allowed to sleep in the hut of one of the wives, as people say?

Makeri: No, no, no. An old man had his thingira, where he would spend the night with his friends. In this case, Makeri and Karuri would spend the night in Makeri’s thingira, where Makeri’s wives would bring them food.

Kariuki: I remembered the horse. Horses were strange to Kikuyu land, where no self-respecting circumcised man would ride a donkey that was easily available. You said Karuri had a horse.

Makeri: Francis Hall, whom people called Wanyahoro, had given him horses to ride so that he could move further and faster.

Kariuki: I marvelled at how progressive Karuri was to own and ride a horse. Karuri was quite westernised then?

Makeri: You know the Kikuyu did not have horses.

Kariuki: But he did not have a carriage for the horses.

Makeri: No. He just rode the horses.

Kariuki: It is written in a certain history book that influential Kikuyus, including Wangu, would bribe Karuri so that he would recommend them to Francis Hall as potential chiefs.

Makeri: That is misrepresenting the facts. For example, you have just offered me a drink, and I have declined. Were you trying to bribe me?

Kariuki: Oh no! It is just normal for people to talk as they drink something.

Makeri: There you have it. Bribing had not been ingrained in Kikuyu culture. You know Wangu was a chief by 1910. She is the one who gave the Europeans land on which to put up the Weithaga mission in Koimbi.

Kariuki: Which church was that?

Makeri: Anglican Church. It is called Emmanuel Church today.

Kariuki: Here I was, learning about a church that goes by the name Emmanuel: Emmanuel! Like me?

Makeri: Are you Emmanuel? I know you as Kariuki. Koimbi is the sub-location. Weithaga is the location. And Muranga is the district. Do you know that is where Kiano was buried—in the Weithaga Church compound? Kiano got money to go to university in America from this church. That is where a ‘harambee’ to raise money was done. Then he came back with an American wife.

(Today, Murang’a is a county after the devolution of Kenya’s Central Government into County Governments.)

Kariuki: I remembered my parents saying that Kiano’s wife was deported as “persona non grata” during Jomo Kenyatta’s presidency; I didn’t know where he was buried. I hear she was a tough woman.

Makeri: Kenyatta helped to kick her out by tagging her ‘persona non grata’. She died just recently, like two years ago. I noticed that she was still using ‘Kiano’ as a surname, as many divorced women do.

(Kiano was a former minister in Kenyatta’s government. After divorcing the American, he married a Kenyan, Dr Jane Kiano, who went on to lead the Maendeleo ya Wanawake Organisation, a national women’s self-help group.

Kariuki: About how many years do you think Wangu ruled?

Makeri: I don’t know, maybe five. What I know is what my paternal uncle told me, and he is not there.

Kariuki: So, can I write five?

Makeri: five to seven years. Write seven. Now ask the last question: I need to go before the rush hour.

Kariuki: I hurry to ask as many questions as time will allow: How did Wangu stop ruling? Was she sacked, or what?

Makeri: Wangu fell ill. Then Ikaya ruled as regent, briefly for her son, Muchiri.

Kariuki: Who was Ikaya?

Makeri: He was part of Wangu’s 'Njama (council of elders). Then, when Jacob Muchiri came of age, he took over as chief. It is this Jacob Muchiri who was my paternal uncle.

Kariuki: I will use this material on the Internet. I like to post interesting things about the Kikuyu. Do I have your permission?

Makeri: By all means, use it. People need to know these things. We need to meet again when we have more time.

Kariuki: Thank you very much. Bwana Makeri.

...........................................................................................................................................................

📘

Want the full version? Ask for the expanded PDF—now featuring five captivating

Kikuyu leaders:

·

Brief biographies of Karuri wa Gakure,

Waiyaki wa Hinga, Kinyanjui wa Gathirimu, Wa Ihũra, and Wangu wa Makeri

·

Cultural insights, proverbs, and

historical context

·

Reader-friendly layout and

educator-ready format

💰 Only KES 300 or 2 USD for the PDF 📩

Email kenatene@yahoo.com or

💳 (or PayPal,

kenatene@yahoo.com)

Preserving

memory. Honoring leadership. Inspiring futures.

Concluding remarks: The story of Wangu wa Makeri, pieced together through historical accounts and the invaluable personal recollections of her grandson, offers a compelling glimpse into a pivotal period in Kenyan history. Beyond the legends and occasional misinterpretations, she emerges as a determined leader who navigated the complexities of colonial rule. James Makeri Muchiri's insights provide a crucial human dimension to her legacy, reminding us of the importance of preserving individual stories to enrich our understanding of the past and celebrate the remarkable contributions of figures like Wangu wa Makeri.

Preserving Kikuyu memory takes time, care, and community support. If this post added to your understanding, Buy Me a Coffee and help keep these stories alive.

References

1. LSB Leakey, the southern Kikuyu before 19032. Mary Wanyoike, Wangu wa Makeri (edited by Prof. Simiyu Wandiba)

Comments

Post a Comment