Who Were the Ancient Thagichu People in Kenya?

Introduction:

The Kikuyu people of Central Kenya, while not explicitly claiming Egyptian origins in their traditions, bear linguistic and cultural threads that hint at a deeper connection. Building upon previous explorations of a potential migration from Egypt, this article delves into the intriguing prevalence of the suffix "Isu" (and its variants like "Gishu" and "Osu") across Bantu and Nilotic languages in East Africa, extending even to the Ibo of Nigeria. This widespread linguistic marker suggests a shared ancestry linked to ancient Egyptian concepts, potentially tracing back to the veneration of the goddess Isis and her associated deities.

The Etymological Link Between Isis and Other Words

The proposed link between the ancient Egyptian goddess Isis and the East African suffixes like "Isu," "Gishu," and "Osu" hinges on potential linguistic evolution over centuries of migration and cultural exchange. One possibility lies in the ancient Egyptian practice of associating individuals or groups with specific deities. This potentially lead some people to identify with Isis, including calling themselves "Of Isis" or "Belonging to Isis." Linguistically, the core sound "Is" in "Isis" could have undergone phonetic shifts common in language divergence, such as vowel changes or the addition/alteration of consonants to adapt to different phonetic systems in the migrating communities. While direct, documented etymological evidence remains scarce, the consistent presence of this sound pattern within communities with other proposed Egyptian connections warrants further linguistic investigation into potential cognates or shared roots.

The Connection with Godess Isis

The Kikuyu are a Bantu-speaking people from Central Kenya. Though their tradition does not claim a Misri (Egypt) origin, I have demonstrated in the hubs – ‘Akhenaten and the Kikuyu’ and ‘Kikuyu people of Kenya: secrets of a migration from Egypt – that they went to great lengths to hide an origin for Egypt.

The Wikipedia states that the Kikuyu language is one of the five Thagichu languages in East Africa. It will be clear from this article that the suffix “Isu” (Ishu) is more widespread than Wikipedia implies, with its tentacles within the Bantu and Nilotic groups of languages and including the Ibo of Nigeria.

There has been a debate in a variety of media about an extinct people called the Thagichu, whom some believe were the proto-Kikuyu. According to this theory, the Thagichu, in their migration, separated into several groups that now form some of the communities within the Mount Kenya region. Currently, to the best of my knowledge, there is no Kikuyu division that goes by the name Thagichu. The term has acquired a negative nuance.

The term Thagichu as used by the Kikuyu has many variants in East Africa. Simon Mulongo, a Ugandan, stated in a comment on HubPages that he hails from the Bamasaaba community, also known as the Bagishu, on the western and southern slopes of Mt Elgon. I have not interrogated Simon in regard to how much Bamasaaba like the term Bagishu but I highly suspect that the community would prefer not to be known as Bagishu. This term is clearly a variant of Thagichu, also spelt as Thagicu.

Ngureco, a prolific online writer, stated in another comment on HubPages that “The name Thagichu is a variant of the names Thagicu (from Mavuria in Mbere and Tharaka), Thaisu (from Kitui), Daiso (from Usambara Mountains), and Segeju (of the northeast coast of Tanzania).” Ngureco goes on to say that “The Thagicu people may have separated due to migration, disagreements, war, witchcraft…”

To advance Ngureco’s observation on the variations of the term, the following terms are synonyms of Thagichu:

Thagichu; Bagichu; Bagisu; Uasin Gishu; Athaisu; Daiso; Osu (of Nigeria)

Muthui Katana, another commenter on HubPages, suggests that the Kikuyu, Meru, Chuka-Tharaka and Embu-Mbeere were one group called the THAGICU or THAICU which later separated into different groups. This makes sense when one takes into consideration the negative nuance to the term which may have motivated the communities going by that term to want to adopt new names. In other instances, two or more groups may have consolidated to form one large unit that was powerful enough to drop the term Thagichu (and its variants) while retaining the freedom to use it on other smaller or disadvantaged communities or clans.

The Akamba, Meru and Their Connection with Thagishu

Among the Akamba community of Eastern Kenya, those from Kitui are called by the rest Athaisu. To these Kitui people, the term Athaisu is derisive and not flattery. Like the Kikuyu, who have retained the term Thagichu in mythology only, there is no Kamba section that will openly state that they are “Athaisu.” Why do the Kikuyu and Kamba people find the term Thagichu (Athaisu) unflattering?

My theory is that the term Thagichu and its variants were used by communities with a superiority complex to subjugate others who had been disadvantaged by being small in number, poor or by other causes after migration from Egypt. Initially, the term was as respectful as any other.

According to a scholar by the name of Ferdiman, the Meru people of the Mount Kenya area, then known as the Ngaa, migrated from the mythical Mbwaa in three divisions. The first division was the "Thaichu (Daiso, Thagichu, Daicho, etc.); the second division "may have been Chagala (Ki-meru: Mathagaia, Mathagala, etc.)... The earlier unity of the Ngaa gradually dissolved, and they entered an era recalled in Meru and Tharaka traditions as "the dividing" (Kagairo). ” Note the use of the term “dissolve” rather than disintegrate and not “disintegration”. Note also that the Ibos have Osu, a variant of Thagichu and Nwadiala, the latter rhyming well with Mathagala.

The Maasai have a district and branch called Uasin Gishu, while the Akamba of Kitui are derisively called Athaisu. Simon Mulongo has explained that the term Gishu was given to them by a Maasai Laibon after the Bamasaaba stole a bull from the Maasai. Gishu, according to Simon, links them to cattle. But since the Maasai are also keepers of cattle, wouldn’t they also be Gishu? Were the Maasai saying that “now that you also seem to love cattle, you are just like us – Gishu?

The Osu Ibos of Nigeria

As can be seen from the foregoing, derivatives of the term Thagishu are common in diverse communities in East Africa. I propose that the word Osu from Nigeria is yet another derivative. The Osu caste system, which has been described by Leo Igwe as “an obnoxious practice among the Igbos – in Nigeria – which has refused to go away despite the impact of Christianity, modern education and civilisation, and the human rights culture.”

The Ibo, according to an ancient tradition, have two classes in their society – the Nwadiala or Nwafor and the Osu. The term Nwadiala has been translated as ‘sons of the soil’, which in other words are the born-free masters. The Osu do not belong to the soil and are therefore outcasts – bondsmen who are descendants of a people who once wielded enormous privileges as servants of the W’iyi goddess or the God Amadioha.

My first encounter with this obnoxious concept was in Chinua Achebe’s No Longer At Ease, where he explains how this thing called Osu came about: “Our fathers in their darkness and ignorance called an innocent man Osu, a thing given to the idols, and thereafter he became an outcast, and his children and his children’s children forever.” The Osu are supposedly unclean since they are deemed to have been dedicated to the gods in perpetuity.

According to Leo Igwe in an online article, the Osu live separately from the Nwadiala, often close to shrines and marketplaces; they are not supposed to associate with or even marry the Nwadiala. Prayers of an Osu on behalf of a Nwadiala or other community gathering are null and void and can only bring bad luck. The Osu caste system was outlawed in 1956, making the ostracism or any form of discrimination against an Osu is a crime punishable by law. Apparently no one has ever been prosecuted in spite of persistent malpractices against the Osu everyday, even by practising Christians, sometimes with the connivance of government officials.

We have seen that the Meru people also had the Thaichu and Mathagala casts before dissolving into one group. This is what the Ibo have failed to do to this day. I believe that a caste system similar to the Ibo one existed among the Kikuyu, Akamba, Meru and other communities in East Africa before they stopped the discrimination, adopted the Thagichu or otherwise metamorphosed from Thagichu by adopting fresh names.

Roots of the Osu/Thagichu in Egypt

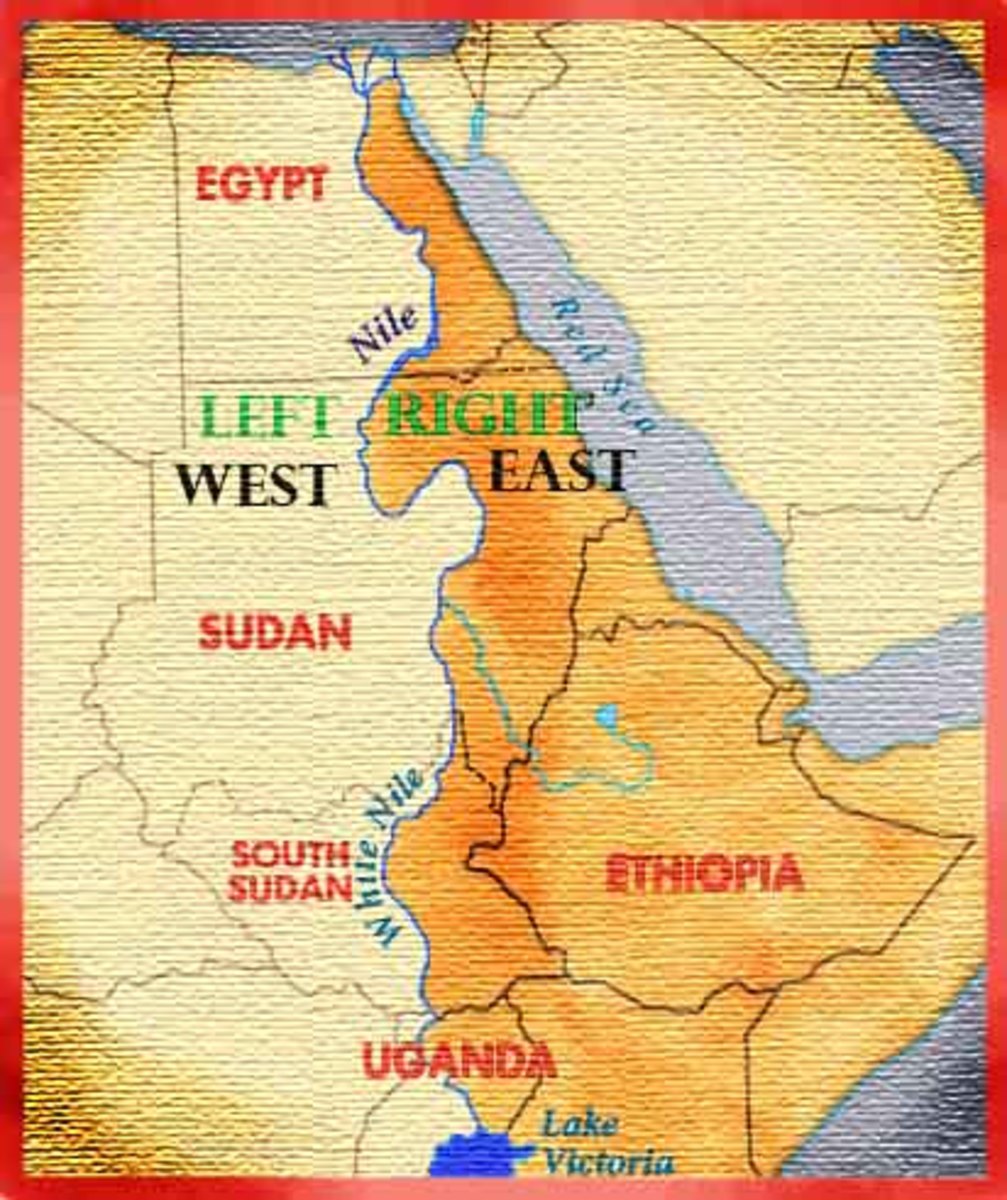

The West (Left) and East (Right)

The River Nile was a natural border between two parts of Egypt – the West and the East. The lands in the East where the sun made its appearance were associated with life, while the lands on the West where the sun set were associated with death and the afterlife. The people living on the Eastern side had occupations associated with the living.

The Westerners - All pyramids, which are in essence royal tombs, are in the West. This is also the left-hand side when you stand facing downriver. The god Osiris judged the dead from notes made by Thoth. He had married his sister Isis. The funerary priests of the West wore masks depicting Anubis the Jackal. Anubis, whose other name was Kenti Amentiu, was deified as a funerary god. Osiris, Isis, Anubis and the term Kenti Amentiu can be expected to survive as linguistic terms in communities that have their origins in the “West”. The tombs had a large workforce to carry out new burials, maintain the tombs and enact rituals in the chapels. These were the Westerners. I highly suspect that it was taboo for the Westerners to farm but they could keep cattle. They took a lot of pride in their professions and kept away from farming, and eventually they came to look down upon farmers and to believe that all cattle belonged to them.

The Easterners – The Pharaoh lived in the East, from where he ruled the state. This is also the right-hand side when you stand facing downriver. Activities related to agriculture and anything else that had nothing to do with death were on this side. The National God was determined by the Pharaoh himself, as can be deduced from the prefixes of various pharaohs shown here in bold text– Amenhotep (Amun), Akhenaten (Aten), and Thothmes (Thoth). The Easterners, as part of their farming activities, could keep a few cattle, but farm activities could not allow them to keep herds as large as the ones kept by Westerners.

Pastoralists, Farmers and the Term Thagishu

As a rule, communities that are strictly pastoralists are practising a Westerner profession.

Communities that are strictly farmers are practising an Easterner profession. Of course some communities may have been influenced to adopt any of the two economic activities from others, so it is not a fast and hard rule.

When the ancient Kikuyu were initiating warriors, they had Left hand side regiments and Right hand side regiments with slightly differing rituals. I propose that this was what had happened in Egypt, where the Westerners and Esterners contributed young men to protect the state in times of war. It is likely that in different periods, the two sides did not agree, causing rifts in Egyptian society. This was solved by a co-regency, the most notable one being Akhenaten (Easterner – right hand) and Smenkhare (Westerner – left hand). This arrangement was so remarkable that it is remembered to this day. Some communities say Kare (Smenkhare) to mean long ago, while others say Tene (Akhenaten) for long ago.

I suspect that after a migration from Ancient Egypt, the society would be in three distinct classes.

On the one hand, there was the ruling class, nobles and their servants from the Eastern side of the Nile. These would form the upper class and owners of soil.

On the other hand, there were the priests and their servants on the Western side of the Nile, which symbolised the setting of the sun and the afterlife. These folk would form the second class, dedicating their lives to serving gods and assisting the living to make a smooth transition into the afterlife.

The third class would be the communities that migrants found in East Africa – such as the Athi/Ndorobo of Kenya or Twa of Rwanda

Let me state from the onset that each migrating community had relatives from both sides – East and West. I suggest that the Kikuyu of Nyeri were predominantly “Westerners”. The word Nyeri also implies that they were the rear guard of the Kikuyu Gathirange (pure Kikuyu) since the word shares a root with "runyiri" – tail feathers used in a dance costume. Among the Meru, the Imenti clan were predominantly “Westerners” (note the similarity with Kenti Amentiu, another name for Anubis, the funerary god). My suspicion is that these Westerners were the Thagichu.

The term Thagichu was not derogatory to begin with since, in Egyptian society, people looked forward to death and an afterlife full of the same abundance that was available on earth. I would suppose that they were maintained by chapel offerings, gifts and probably a special tax. However, upon migration, things must have turned out very different. There were no royal tombs and therefore no offerings or gifts to maintain them. It is unlikely that the Easterners could generate enough work to sustain the Westerners in East Africa and elsewhere; hence, the distinct lifestyles of pastoralism (Westerners) and farming (Easterners). The association with death and spirits of the departed is what gave a negative connotation to any term associated with the Westerners.

Where the Westerners were the majority, they looked down upon the Easterners as a poor people with no cattle.

Where the Easterners were the majority, they looked down upon the Westerners as poor people with no farm produce. Discrimination went both ways until the term “...Gishu” lost significance in East Africa.

Initially, each of the two groups preferred to marry only among themselves, thereby entrenching their differences. However, this was not always possible where one group was too small. The Kikuyu, by having two variants in their ceremonies called the Kikuyu guild and the Maasai guild, respectively – one for the right (Kikuyu – Easterner) and one for the left (Maasai – Westerner) – found a way of unifying the opposing elements, and therefore discrimination was halted.

I highly suspect that the ritual of the second birth described in another hub also served to remove a person from the minority group to the majority group for full citizenship. Eventually society forgot the original purpose of the ritual. In other words, the Westerners and the Easterners had to invent a formula to forge themselves together. The Meru, as we have seen above, dissolved their two original migrant groups (Westerners and Easterners) into one cohesive tribe. Among the Ibo, a formula was never found, thereby subjugating the Osu to a life of perpetual ostracism that has persisted to this day.

The God Isis and the Term Thagishu

Taking note of the fact that Nigerian Osus were dedicated to the gods, the word Isis of Ancient Egypt appears to share a root with the word Osu. From a linguistic point of view, her brother Osiris is not too far in line. It is also noteworthy that the Nandi of Kenya, who would fall in the category of “Westerners”, use the word “Asis” for God.

Isis, a daughter of Thoth, is depicted as a winged goddess and was one of the ‘Nine gods of On’ – the ennead. Having married her brother Osiris, she was also a queen. The complete list of gods in the Ennead is as follows:

Atum-Ra, 2. Shu, 3. Tefnut, 4. Geb, 5. Nut, 6. Osiris, 7. Isis, 8. Seth, 9. Nepthys.

Note that the Kikuyu have nine clans, which may be an indication that each clan was dedicated to one of the gods in ancient times. The Ibo of Nigeria have “Nine villages of Umuofia”.

Osiris, the god, and Ra were identified with the willow and the sycamore trees. A picture exists in Egypt where Thothmes III “is shown being nursed at the breast of ‘his mother Isis’ in the form of a Sycamore tree.” Those who dedicated their work to Isis may as well have called themselves “Of Isis” with different variants as listed – Thagichu, Bagichu, Bagisu, Uasin Gishu, Athaisu, Daisu, and Osu.

The earthly attendants of the “Nine Gods of On” are therefore the origins of “the Nine villages of Umuofia in Nigeria; the Mijikenda (nine villages) of the Kenya Coast; and the Nine clans of the Kikuyu and the reason why the number 9 is sacred in many African communities. As can be seen in the story of Isis, the sycamore tree (Mukuyu) was as significant to the Egyptians as it is to the Kikuyu, who derive their tribal name from it.

Concluding Remarks on the Thagishu

In conclusion, the Egyptian goddess Isis and her brother Osiris are represented in the term Thagichu (and its many variants, such as Daisu, Osu, etc.). The migrants from Egypt were in two main classess – the Easterners (right hand) and the Westerners (left hand). A feeling of superiority persisted in the group that was numerically large. The larger group naturally discriminated against the smaller group. It would appear that in some cases, a Western community was large enough numerically to be the overlords.

Within East Africa, Thagichu and its variants remain only in myths. I interpret this to mean that the Westerners were either numerically inferior or their reliance on the Easterners, who were farmers, increased, which led them to accept adoption and integration. Their previous profession of funerary activities in Egypt also contributed to the negative nuances in the terms that they used previously and hence the need to discard them.

References

Achebe, C., 1958, Things Fall Apart, Heinemann, London.

Discrimination by Leo Igwe: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leo_Igwe

Nyaga, D., 1986. Meikariire na Miturire ya Ameru. Heinemann Educational Books, Nairobi.

Ogot, B.A., editor, 1974, Zamani, a Survey of East African History, East African Publishing House, Nairobi.

Ogot, B.A., editor, 1976, Kenya Before 1900, Eight Regional Studies, East African Publishing House,

Preserving Kikuyu memory takes time, care, and community support. If this post added to your understanding, Buy Me a Coffee and help keep these stories alive.

Disclaimer

The information presented in this article is intended for educational and cultural enrichment purposes. While care has been taken to accurately capture Kikuyu traditions, this article does not claim to represent every scholarly interpretation.

Readers are encouraged to consult additional sources or native speakers for deeper insights.

Kikuyu Culture & History respects the diversity within Gĩkũyũ-speaking communities and welcomes thoughtful dialogue. If you notice any inaccuracies or have suggestions, feel free to contact us at kenatene@gmail.com.

Comments

Post a Comment